Response to Dr. Block’s “Biology, not free enterprise, at fault for pay gap”

August 21, 2017

BY NAOMI YAVNEH KLOS, PH. D.

DIRECTOR OF THE UNIVERSITY HONORS PROGRAM

First, I’d like to applaud the editors of The Maroon for publishing Professor Walter Block’s editorial. Publishing such a controversial and “politically incorrect” piece at a time of tension and pain over systemic inequity and racism demonstrates what we are committed to teaching here: that is, to listen, respectfully, to others with divergent opinions.

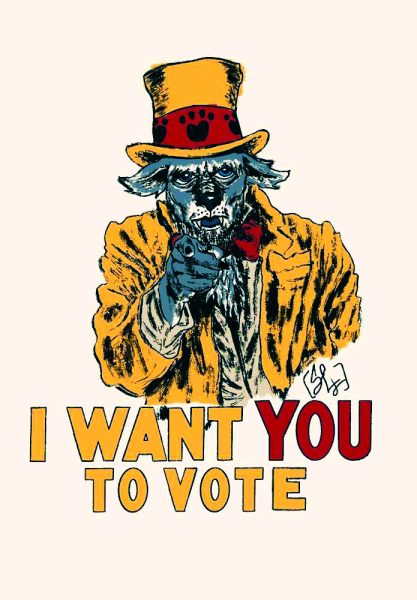

And so I respectfully respond to Dr. Block that his opinion, “Biology, not free enterprise, at fault for pay gap,” ignores a key factor: the systemic oppression of women. Historically, in this country and elsewhere, women were denied access to education, employment and suffrage on the basis of their gender. Indeed, in an irony probably unnoticed by The Maroon staff, Dr. Block’s editorial was published on August 18, 2017, 97 years after the so-called “Susan B. Anthony” amendment (the 19th) finally granted women the right to vote, 240 years after suffrage was granted to white, propertied men by the constitution and almost 50 years after the 15th amendment affirmed that “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color or previous condition of servitude.”

The historic lack of access to education for women, I would argue, is a far more important factor than biology in the underrepresentation of women in science, technology, engineering and mathematics. Although New Orleans’ own Ursuline Academy was founded in 1727, the first public schools for girls did not open until 1826, in New York and Boston. And while institutions of higher learning existed in the United States long before the revolution (my own alma mater, Princeton, was founded in 1746), women – even white ones – were denied access to colleges and universities until the 19th century. Oberlin College, originally an abolitionist institution chartered in 1833, accepted men and women, including African-Americans. Vassar College, the first women’s college and my mother’s alma mater, was founded in 1861, at the beginning of the Civil War.

That doesn’t mean that access was available to all or that women’s education was considered acceptable. Often, it was considered antithetical to the mission of motherhood. My grandmother, an immigrant from Romania raised in New York City, told me of the party they held for her second-grade teacher, who had to resign because she was getting married. Grandma went on to attend Hunter College, a public women’s college in New York originally founded as a teacher-training institution, where she majored in math because they only had a physics minor. Already married and seven months pregnant when she graduated in 1932, she was terrified that she would fail the physical examination required of all graduating seniors, because being pregnant was cause for dismissal, regardless of marital status. (Fortunately, she was assigned to the one female doctor, who simply ignored the baby bump that was my mother.)

But irked as she was that she couldn’t study her preferred major, my grandmother, a poor, Jewish immigrant, was privileged by her access to college, and, indeed, by the encouragement she received to pursue the “masculine” fields of math and science. Is it surprising that we have more female beauticians than construction workers when, even in the 1960s, it was still a norm to require “shop” for boys and “home ec.” for girls? And one of our current female physics pre-health majors told me that she chose Loyola because it was the only school that didn’t assume she wanted to become a nurse.

Not only has access been denied, the accomplishments of women in the sciences have often been hidden, as the recent film “Hidden Figures” reminded us, uncovering the forgotten but essential role of NASA’s African-American female mathematicians. And Walter Block is right that more men have won Nobel prizes, but many students of biology would agree with me that Rosalind Franklin should have been acknowledged for the double helix, along with Watson and Crick.

Physiology does control many parts of our lives. While my husband, at 6’7’’, has strength to lift double my weight, I have given birth to four children, a miraculous (and quotidian) physical accomplishment limited only to women. But it is specious to mistake the historic, systemic conceptions of what our physical abilities and limitations entail for a biological imperative of inequality.

Dale Holmgren • Jul 8, 2019 at 1:24 pm

I believe Dr. Klos is missing Dr. Block’s point. No one could reasonably argue that today’s college student is prevented from choosing any major of her choice due to her gender. Indeed, women do choose to go into all majors, as you can see in the link below. However, even today, an overwhelming number of women choose – SHOCK – nursing, and only a tiny fraction choose electrical engineering. What, don’t they know that electrical engineers are paid more?

Women choose for a career what they want to do, or perhaps they choose what they feel they CAN do that fits in with future motherhood. How many mothers choose to be mining engineers working in the Yukon? Dr. Klos’ argument would have been better served had there been ZERO female mathematics majors – perhaps then it would have been worth examining whether there was oppression.

https://inside.collegefactual.com/stories/the-most-popular-majors-for-women-men